Reviewed by Justin Goodman

Reviewed by Justin Goodman

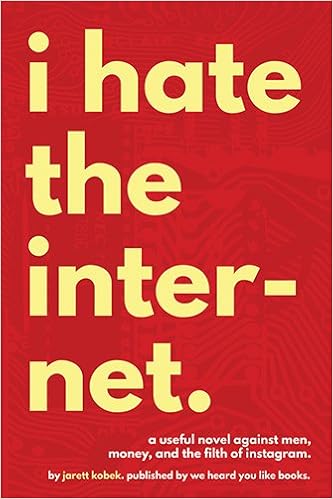

I Hate the Internet

by Jarett Kobek

We Heard You Like Books

Paperback: 288 pages, February 9, 2016, ISBN-13: 978-0996421805

Most nights I spend at Starbucks because its anodyne environment—benign jazz-pop, youth in plaid fleeing weltschmerz, wrinkled men with newspapers reenacting advertisements from the ‘50s—acts like a “non-place.” A non-place is a bullshit phrase coined by French anthropologist Marc Augé as a way to explain why people aren’t as obsessed as Marc Augé with where they are all the time. It’s where you’re surrounded by things you hate so much that you maneuver through it in a numb, near-catatonic state. Airports and supermarkets and coffee shops. It’s funny that I’d decide to read Jarrett Kobek’s new book (not-)there. The vitriol of I hate the internet is the misery of the bourgeoisie, almost all of which “lack eumelanin in the basale strata of their epidermis” (as Kobek repeatedly describes whiteness); I sympathize regardless of my eumelaninlessness. More than being a prolonged expletive flailing absurdly about like a verbal Bernie Dance though, this self-described “bad novel” is a madcap, mad-dog, remonstration of Post-Industrial America. With the distance of an anthropological past tense, cynical wit nipping as Ambrose Bierce’s Devil’s Dictionary, and macabre examination of socio-politics, the closest experience must be that of an existentialist who walks into a bar only to realize the essence of his decision is a joke.

Let me start by saying that this is not the priggish culture-comedy of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight Children wherein the oracular novelist jeers at India’s language obsession with an “unbelievable ability to pick on the powerless” comparable only to the Twittersphere. Superficially I hate the internet has the chaotic leitmotif of Midnight’s Children—Jack Kirby, packet switching, and venture capitalism occur with the regularity of knees, noses, and snakes—as well as the PoMo reflexivity that insists literature is about pedagogy. But Kobek is a true novelist of the 21st century. His deadpan definitions trust the reader is contemporary (“the iPad was an iphone with a bigger screen and no ability to function as a phone”) or is competent enough to Google (“But Lancelot wasn’t a unicorn. Lancelot was a goat that had been tortured by the person [Morning Glory Zell-Ravenheart] who would later invent the word polyamorous”); the story of the famous comic artist of Trill, who has adopted a Transatlantic accent for unknown reasons, interacting with the perversity of social media and her friends, who range from a transgender woman in the tech business to Trill’s black co-author now working in video game storyboarding, balances zaniness and humor perfectly. Yet there is hope against hopelessness, even with a “plot, like life, [which] resolves into nothing and features emotional suffering without meaning.”

There are moments when the paradox of the embittered subsumes the critic, sure. When Adeline, the artist, is recorded criticizing Beyonce and Rihanna to a writing class the professor had invited her to speak at, she is bombarded with the hatred of their fans. A familiar moment defined by Kobek as the fans “teaching Adeline about how powerless people demonstrated their supplication before their masters.” There’s also the burden of the over-repeated, no matter how boldly stated. Who doesn’t know that “the treatment of the indigenous people of the United States was the world’s biggest genocide?” What writer doesn’t suffer some thought that “the creators of culture had no impact on anything. The only thing writers were good for was sending messages across time?” I want to hear about today’s deities, what writers are good for. Adeline’s transgender friend Christine slips in. “Google wants us to believe they are changing the world…All Google does is serve advertisements.” “They are liars,” she adds, “and I pray to liars.” The next paragraphs are an outline of “all the founders and key players in Silicon Valley as new gods”: Larry Page is the tepid Hephaestus, Sergey Brin the erotically charged Dionysus, Steve Jobs is Hades. None of the reasons are flattering.

When the experimental poet Kenneth Goldsmith read “The Body of Michael Brown” last year in the most impressive display of intolerable bullshit the arts have funded, fires burned on the horizons of Facebook, Twitter, and Tumblr for days. The poem was an autopsy report with the scientific clarity removed. It’s Goldsmith’s “uncreative writing” which represents the dilemmas of the 21st century. “The creators of the harvested material had very little say” is how Kobek describes Buzzfeed’s articles. Somewhere along the way, Americans turned freedom of expression and freedom of speech into copy pasting the labor of others for the profit of the already rich. Meanwhile, every controversy, especially regarding perceived or explicit racism, “allowed for more advertisements.” When the road to hell is paved with good intentions and billions of dollars in ads, it’s impossible not to be pessimistic. Nicely summed up, these “moral scolds” “were typing morality lectures into devices built by slaves on platforms of expression owned by the Patriarchy, and they were making money for the Patriarchy. Somehow this was destroying the Patriarchy.”

So, after delivering an angry parody of John Galt’s 60-page speech in Atlas Shrugged from the nouveau sublimity of California’s Twin Peaks, Kobek’s ostensible stand-in, brushing off his hands, says “that’s all I’ve got.” “How do you feel,” Adeline asks. “It didn’t really do much. I guess it was worth a try,” J. Karacehennem replies. A sentiment that’s hard to disagree with, for better or worse. A Chinese tourist stares at him. Like a whisper, we are told her father has become powerful by “enslaving his countrymen and making them build consumer electronics.” She says something in Cantonese, which is translated for us as “fuck you till you fall down in the street, foreign devil.” Does this matter to a man leaving his gentrified hometown with the rancor of the ideologically and literally dispossessed? Does this matter to one who has dedicated their time to the writing? “Words were not power,” Kobek says. A sentiment that’s hard to disagree with. For better or worse.

About the reviewer: Justin Goodman graduated from SUNY Purchase with a B.A. in Literature. Having moved from Long Island, he now lives in the City with reviews in Cleaver Magazine and InYourSpeakers, and work in Italics Mine, 360 Degrees, and Counterexample Poetics.