Reviewed by Sara Hodon

Reviewed by Sara Hodon

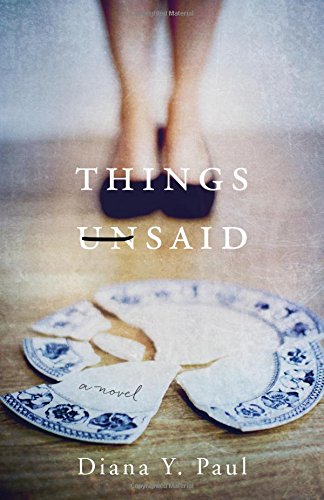

Things Unsaid

by Diana Y Paul

She Writes Press

Paperback: 270 pages, ctober 13, 2015, ISBN-13: 978-1631528125

Many adult children face the same dilemma—feeling torn between loyalty to their created family of a spouse and children, and a certain amount of obligation to their blood relatives, whether parents or siblings. In her debut novel, Things Unsaid, Diana Y. Paul explores these complicated ties that bind.

The plot focuses largely on the protagonist Julia, or Jules as she prefers to be called, the intelligent and practical oldest daughter in a family of three children. Jules is carrying a heavy burden. She herself is at a professional crossroads—a psychologist, she was denied tenure at the university where she’d been teaching, and was now working for a local school district but hoping to finish and publish a book. At the same time, she is trying her best to be a supportive wife to her husband Mike and help her college-age daughter Zoe navigate the often-rocky waters of applying to schools. On the other hand, she feels obliged to remain the dutiful eldest daughter and reliable older sister, always willing to “bail out” her parents and younger siblings. In this case, Jules has a particularly difficult balancing act. Her aging parents refuse to face the reality of their situation. Her vain, high-maintenance mother insists on maintaining a certain lifestyle standard, starting with a pricey residence in a retirement community although it’s quickly moving out of their price range, and her retired doctor father—no match for his narcissistic, strong-willed wife—is struggling with the early stages of dementia but refuses to give up the notion that his stock portfolio will solve all of their financial problems. But it doesn’t, and they find themselves in worse shape than before.

Paul presents a solidly-written cast of characters who are relatable in their imperfections and sense of duty to both their blood and created families. Readers are sure to recognize at least a trace of their own family dynamic in these characters. There are some standard traits in the siblings based on their birth order: Jules, the steady, bookish older sister who dutifully accepts the role of parental caregiver until she takes a closer look at her own family’s needs; Andrew, the middle child and only son who is adored by his mother and equally misunderstood and mistreated by his father, and Joanne, the sweet baby sister with a penchant for plastic surgery whose life goals and low self-esteem closely mirror that of their mother. Paul dedicates at least one chapter to exploring the back story of each character in order to put their relationship to each other in proper context.

The matriarch, Aida Whitman, is a former nurse whose real dream in life was to be a nightclub singer—a dream sidetracked by marriage and children. Her desire to be the center of attention never goes away; she simply finds new ways to be in the spotlight, whether it’s performing at the retirement community’s annual talent show or refusing to compromise her standard of living. Her husband, Dr. Bob Whitman, seems uncomfortable with his place in life and some of his decisions—again, it seems as though most of the choices he’s made stem from a sense of obligation or a desire to be someone other than his true self, not from what he actually wants. Paul skillfully paints their marriage as one that’s not unhappy, exactly, but definitely unfulfilling—both spouses are painfully aware that their own lives have been lacking, and that has broken something between them that they feel but never address. Rather, they muddle through their own careers, marriage, and child rearing as best they can. But their own dissatisfaction taints their marriage and, by extension, their relationship with their children well into adulthood.

I appreciated the fact that Paul chose not to make any of her characters full-on slacker types, or ne’er-do-wells, who simply expect others to take care of them and clean up the problems they create for themselves. Rather, they are flawed and completely relatable individuals, which makes the story all the more compelling. By all accounts, the Whitmans—parents, children, in-laws, and grandchildren—are upwardly mobile. Besides the parents’ professions, Julia is a psychologist, Andrew is a dentist, Joanne owns her own jewelry business, the grandchildren are all making good grades and have their sights set on some kind of future. True, they all look to Jules to “fix” every difficult situation, but I think the oldest child in every family has to take on that responsibility to a certain degree, whether it’s as executor of the parents’ will, the first one notified in case of a medical emergency, or some other capacity. The common thread running through the many financial crises in the book is “Jules will take care of it”, “Jules will fix it”, “We can always count on Jules.” The siblings handle their own domestic situations as best they can (and the parents are secure in the knowledge that their firstborn will always help them, simply because that’s what the firstborn does), but they sleep just a little better at night knowing that Jules has their collective back. This is especially true when Jules is the only member of her immediate family to receive an inheritance from her uncle, her father’s older brother who always favored her. Naturally, she’ll be sharing some of her wealth with them, won’t she? That would solve so many problems for all of them.

And that’s true, until the day Jules takes a long, hard look at her own husband and daughter and realizes that they need her, too, and that maybe, just maybe, she’s been taking them for granted just a little too long. Before she realizes it, her home life starts to unravel and she has to make some important choices. This is a critical scene in the book—prior to this moment, it could be easy to categorize Julia as a doormat or people pleaser, so when she does decide to reassess her priorities, readers will find themselves sitting up a little straighter and maybe turning pages a little quicker to see how she handles her dilemma.

Unfortunately, those enabling the situation don’t change until they are forced to. After a series of health-related events forces many of them to reevaluate their codependence, Jules’ family (both immediate and extended) have to make some big decisions. Again, this is a harsh reality that many adults find themselves experiencing—life events jolt them out of passivity and into proactivity. Things Unsaid is a true-to-life novel that will make the reader ask themselves some tough questions, like “What is your family?” “Is (and should) blood be truly thicker than water?” And finally, “When is enough obligation enough?”

Although I didn’t truly dislike any of the characters throughout the novel—probably because I found them so relatable and I could sympathize with so much of what they were going through—I had a newfound respect for the adult children by the end.

About the reviewer: Sara Hodon is a Pennsylvania-based freelance writer whose work has appeared in over two dozen print and online publications.