Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

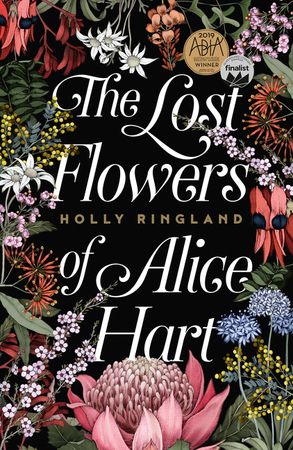

The Lost Flowers of Alice Hart

by Holly Ringland

HarperCollins (4th Estate)

ISBN: 9781460754337, 19 March, 2018, 400 pages, $32.99aud

It’s impossible to write about The Lost Flowers of Alice Hart without talking about how physically beautiful the book is. While it may be true that you can’t judge a book by its cover, this one is a striking William Morris style floral cover. The inside, with each chapter represented by a flower, beautifully drawn by botanical artist Edith Rewa, with titles designed to look handwritten. Somehow the book manages to be both lush and delicate, and the story is the same, peppered throughout with poetry, including the beautiful “Seed” by Ali Cobby Eckermann from My Mother’s Heart, as well as excerpts at the start of each section from Tennyson, Sappho, Emily Bronte, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Alice Hart is a compelling protagonist, beginning her story as a nine year old girl in a dangerous domestic violence situation, immediately clear from the purple bruise and split skin of her mother’s face: “The only signs she would need to read would be in the sky, rather than the shadows and clouds that passed over her father’s face, alerting her to whether he was a monster, to the man who turned a gum tree into a writing desk.” (6/7) Alice grows through this coming-of-age story, moving through the teen years and first love to independence at twenty six years as she attempts to come to terms with her violent upbringing and the disaster she has endured as well as the many secrets and gifts that underpin her life.

The story’s settings are richly depicted, from Alice’s original home amidst sugar cane and the ocean, to a native, inland flower farm/refuge to a national park in the Northern Territory where Alice obtains a job as a Ranger. The natural environment is as much a part of the characterisation as the people – with the ocean, the river, the red desert earth and the stunning sunsets:

Around them, the willowy needles of desert oak trees swayed in the pale orange light. Wafts of yellow butterflies fluttered low over acacia and mulga bushes. The crater wall slowly change colour as the sun sank, from flat ochre to blazing red to chocolate-purple. The sun slipped under the dark line of the horizon, glowing like an ember as it threw its last light into the sky. (241/242)

There is a kind of magic that is woven through the book, primarily from the language of flowers that works in conjunction with the semantical story but has its own silent meaning. Flannel flowers mean “what is lost is found”, Sturt’s Desert Peas, which are integral to the plot, mean “Have courage, take heart”, and Foxtails mean “Blood of my blood”. These flowers become Alice’s language when words fail her. They work as subtext in conjunction with a range of other intertextual elements like the poems, the fairy tales that are referenced, and the stories from other cultures brought in via characters like young Alice’s Koori carer Twig, for whom Alice becomes a surrogate child, Alice’s Mexican friend Lulu, the Bulgarian fairy tales of Boryana, whose son becomes Alice’s first love, and the poet, artist, law woman and senior ranger Ruby, who teaches Alice the story of the heart garden, and about the power of story to heal:

Ruby stood on her patio in the setting sun, watching rainbows catch in the spray while she watered her pot pants. The mineral-rich smell of the damp red dirt took her straight to the memory of her mother and aunties, like a song. The sky gathered a palette of pink clay, ochre and grey stone. (259)

Though the story moves quickly, carried mostly by Alice’s attempts to escape her past, the writing itself is continuously poetic, filtered through the prism of Alice’s point of view. The writing remains beautiful, even when describing the most appalling abuse, as when Alice’s father pushes her off a boat into the ocean for missing a command to hula at a passing stranger:

The pressure on her back was firm and quick. She pitched forward into the cold sea, crying out a she was engulfed by waves. Spluttering to the surface, she shrieked and coughed, trying to hack up the burning sensation of salt water in her lungs. Kicking hard, she held her arms up the way her mother taught her to do if she eve got caught in a rip. Not too far away, her father coasted on the board, staring at her, his face as white as the caps on the waves. (32)

There are many themes running through this book, but the most prevalent is power of books and language – not just words – to heal. For Alice, books open up her world and provide her with a key to finding herself. Male violence crackles through the book and moves like a malevolent force, forming a parallel line from Alice’s father to her later male relationships. Though Clem and Dylan are unequivocally bad, Ringland crafts them with sympathy, focusing more on the critical importance of support networks like female friendships to change negative patterns and create healing and awareness. In spite of all the loveliness, The Lost Flowers of Alice Hartis not a meek book. The story travels into dark places, and sheds light on a very serious and significant subject with grace and beauty.