Reviewed by Michael T. Young

Reviewed by Michael T. Young

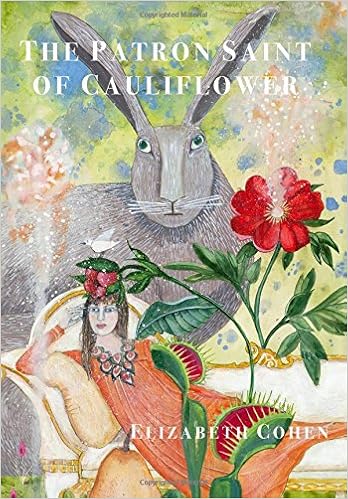

The Patron Saint of Cauliflower

by Elizabeth Cohen

Saint Julian Press

June 2018, 80 pages, $16.00, ISBN: 978-0-9986404-8-8

M.F.K. Fisher said, “There is a communion of more than our bodies when bread is broken and wine drunk.” This is an apt quotation to keep in mind entering Elizabeth Cohen’s new poetry collection, The Patron Saint of Cauliflower, for it is a collection about a lot more than food and even how it can, in some ways, unite us. More than that, this collection is about magic and believing, about transforming hardship into meaning, about having a way to handle the pains that will surely come.

In the title poem that lists a kind of descriptive dominion of the saint, we are told

and all of this from the tiniest brassica seeds,

small as the clipped fingernails

of your kitten (“The Patron Saint of Cauliflower”)

Brassica are of the genus of plants in the mustard family and thus recall Jesus’ words to the disciples in Matthew 17:20, “If ye have faith as a grain of mustard seed, ye shall say unto this mountain, remove hence to yonder place; and it shall remove; and nothing shall be impossible unto you.” Such faith is a necessary ingredient in a collection that also, in it’s opening poem, “Goulash,” has the speaker thinking of feeding her children and their friends warning us that

Someday, they will encounter bullies

they will feed their own parents soup,

and possibly hold someone’s hand as they die

They will have many paper cuts

which is to say they will bleed

The poems show us both the necessity of facing those paper cuts and the many forms they take, great and small, but also the folly of ignoring them, of anesthetizing ourselves to the reality of suffering. In the poem, “Margarine (Packaged So Beautifully)” the poet imagines the butter substitute as the name of a girl, imagines her life in which

She will be just right. She will be ready for all the happiness

promised to us. Two cars, two sons. House, yard,

dinner every night at six.

But this perfection is a lie, it’s a fantasy that doesn’t prepare for the failures and tragedies that will come. It contrasts with the children in the opening poem where the speaker feeding them explains,

I like to think I am feeding them a few ways

to prepare for the end of the world here

or again, in the closing of a poem that is tellingly titled “Paper Cut,” we are told

this is the world

beauty can trick you

you have to be ready

you have to have a plan

Or a recipe, which, within the context of the collection, also serves as a kind of magic. There is a “Spell for the Right Avocado,” a “Spell for the Layer Cake,” a “Spell for the Very Best Pesto.” These are not hocus-pocus but many ways we have of drawing peace out of chaos, of providing and uniting. As the poem “Apples” tells us,

Produce from warring nations could make peace

in our molded gelatins

and soybean bakes

topped off with butter from Minnesota

In this way, the collection reminds one that war and peace in the world is an intimate thing, not solely the province of political figures in suites sitting in offices of power, but of mothers and daughters learning to nurture each other, of husbands and wives caring for each other. There is a point in the collection where the private and the public come into conflict within the realm of political speech. A poem called “Political Speeches,” shows how political language tries to emulate the power of religious faith, it wants

. . . you to follow

with a spirit longing

as to fresh chants

of Buddhist eldersthey might ask you to tithe

in blood

and sometimes, offerup a first born

It is a powerful political poem and among my favorite poems in the collection. As it concludes, it shows that those who refuse to fall in line with such political speech are lumped in with rebels, people who are

masters of the art

of political deafness

who would rather listen

to the annual songsof geese, or the weep

and cry of storm windows

in the wind

It’s this conflict between larger forces in the world and the individual life that surfaces throughout the book and even within individual poems. In “Asparagus, in a Fig Sauce” where the speaker explains, “Your mama’s china, not a chip/How you fought with her, sobbing for years,” goes on to a larger parenthetical insight:

(All the world over

People are wondering

Whether to eat dirt or

Suck on a stone)

One can feel this intrusion of public into private even in the style of these poems. Most of them, though not all, dispense with typical punctuation: no periods or commas. Capitalization marks a new sentence, while lineation and syntax provide the proper pacing. One is never lost in navigating the sense of the poems, which is remarkable for a style that is paradoxically sweeping and spare.

The final poem of the collection returns us to the private. The collection opens in “Goulash” where the speaker is feeding and teaching children how to endure suffering. In the final poem, someone is facing the suicide or attempted suicide of a daughter

All you know is that you tasted

your baby’s blood that afternoonwhen she opened her wrists

and it tasted of sour mash, of salt marshof all the mistakes you had ever made

Salt is the ingredient and title of this final poem that ultimately tastes “like secrets.” This recalls an earlier poem in the collection, “Poem for the Little Finger,” where a mother and daughter “pinky swear” and it is meant that they are

Not to lie

Not to tell

Secret kept

And something of secrets—what to reveal, what to conceal—also runs throughout the collection. Secrets are intimacies, and we the reader are let in on some. But some secrets when told are betrayals, or suicides, blood spilled or spells cast, for magic and saints governing and protecting, are also secret languages, the ancient rites of certain religions also called “mysteries.” And, so it is in this well-balanced and short collection, an excursion into mysteries, methods of preserving and enduring. It is a beautiful collection that carries us along with the assurance of the heart behind it, and imparts to us methods and meanings that are a way of dealing with those paper cuts, those times we bleed.

About the Reviewer: Michael T. Young‘s third full-length collection, The Infinite Doctrine of Water, was published by Terrapin Books. His chapbook, Living in the Counterpoint (Finishing Line Press), received the 2014 Jean Pedrick Chapbook Award from the New England Poetry Club. His other collections include The Beautiful Moment of Being Lost (Poets Wear Prada), Transcriptions of Daylight (Rattapallax Press), and Because the Wind Has Questions (Somers Rocks Press). He received a fellowship from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and the Chaffin Poetry Award. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in numerous print and online journals including The Cimarron Review, The Cortland Review, Edison Literary Review, Lunch Ticket, The Potomac Review, and Valparaiso Poetry Review. His work is also in the anthologies Phoenix Rising, Chance of a Ghost, In the Black/In the Red, and Rabbit Ears: TV Poems. He lives with his wife and children in Jersey City, New Jersey.