Reviewed by Sara Hodon

Reviewed by Sara Hodon

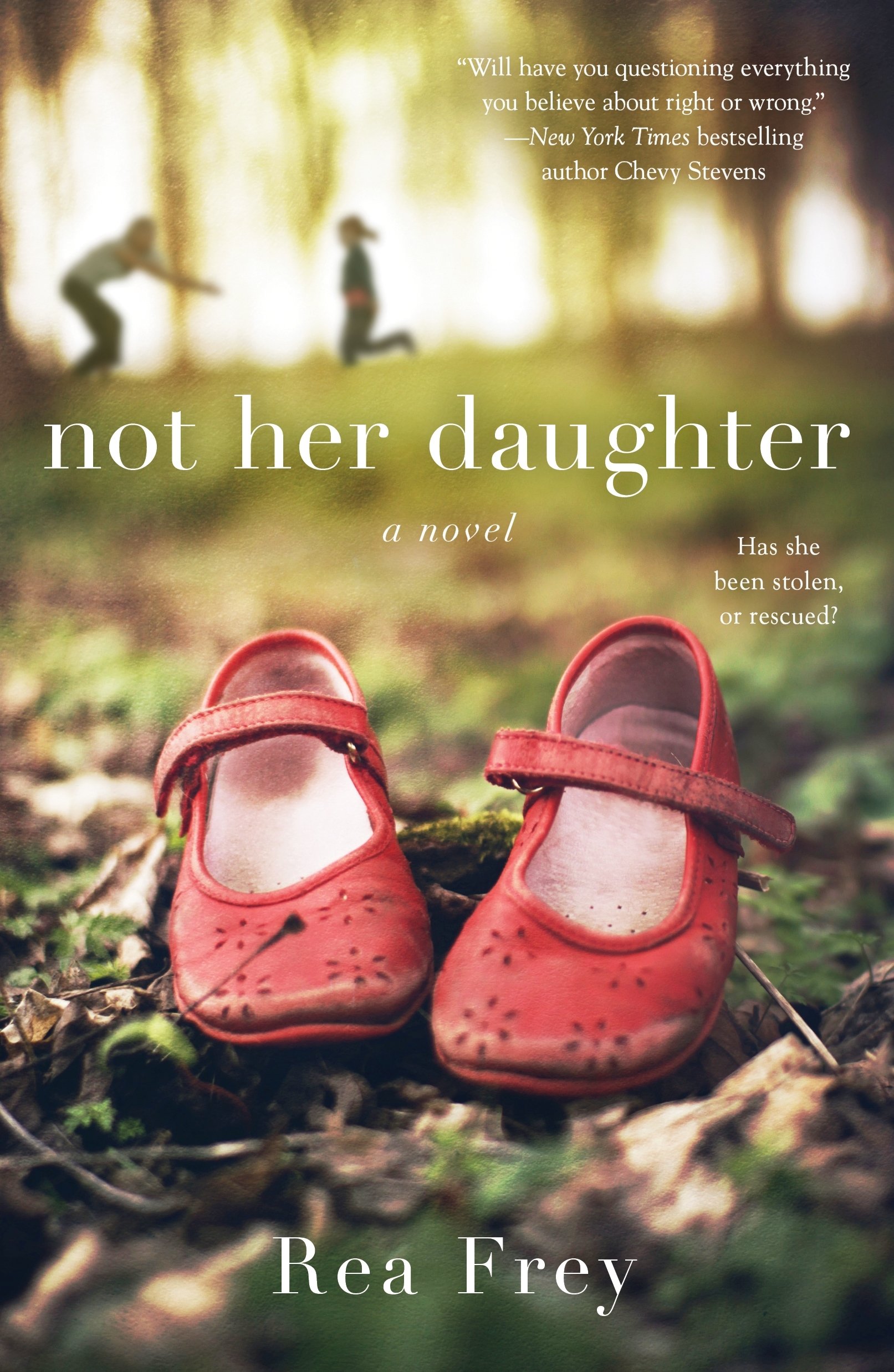

Not Her Daughter

by Rea Frey

Griffin

Paperback: 352 pages, August 21, 2018, ISBN-13: 978-1250166425

Being a parent, especially a mother, is arguably the toughest, most rewarding job in the world. Most mothers accept the ups and downs as all part of the experience. But there are some mothers who frankly aren’t cut out for the job—their naturally prickly personalities are just magnified by their children’s mercurial moods, creating stress and tension on all sides. These women find themselves wrestling with the questions “What if I’d never had children? Would I be happier without them?”

This is the premise behind Rea Frey’s debut novel, Not Her Daughter. Amy Townsend is a bitter, exhausted, overwhelmed mother of two, but has a particularly difficult time with her 5-year-old daughter, Emma. She is perpetually unhappy with the choices she’s made. Where other women might envy her life—a steady marriage, healthy children, and stable job—Amy is bored and restless, feeling as though she’s “settling” but not entirely sure what else might be out there for her. She’s unhappy but not sure why, so she’s just stuck in a life she feels she didn’t choose.

Sarah Walker is a single, career-minded entrepreneur focused on building her business. She’s also dealing with some heartache. She’s nursing a recent breakup, and the lingering sting of her mother’s abandonment when Sarah was a child colors everything she does. While waiting for a flight, Sarah notices an exchange between a stressed out, impatient mother and her wary daughter—a scene not unlike the millions that take place between mothers and daughters every day all over the world—but something about this mother and daughter stays with Sarah. The girl’s striking looks (particularly her unusual grey eyes) and the mother’s hopelessness masked as anger and impatience remind Sarah of her own difficult childhood with her impossible-to-please mother. Amy and Emma go their way with their family, Sarah goes hers. But Sarah can’t forget the little girl. By sheer coincidence, Sarah’s business takes her on a trip to Emma’s Montessori school. Sarah sees it as a second chance to help the girl, and slowly a plan forms in her mind. She begins to keep a closer eye on the Townsend family. One night, when Amy locks Emma out of the family’s home as punishment, Sarah seizes the opportunity to lure Emma away.

The chain of events that follow set off a list of moral and psychological issues for the characters, but readers will likely find themselves questioning what they would do in a similar situation. In Sarah’s mind, she’s doing the little girl a favor—taking her away from a cruel mother, a father who pays little attention to her, and generally giving her a chance at a happier life. Amy is torn with her feelings of guilt—why did she lock her daughter outside? What kind of mother would do that?—and yet a sense of relief. She is concerned for her daughter’s well-being in a superficial sense, but when she is being honest with herself, she’s not terribly upset that Emma’s gone. The motherhood thing is just so hard for her, she would argue. Amy admits to dressing Emma in the same clothing every day to avoid arguments over getting dressed. It’s just easier. Maybe the girl is better off without her. Every mother has feelings of inadequacy at times, but to be relieved that your child is taken from you…that brings an entirely different level of morals into question. As a reader, I didn’t notice any unusual mother/daughter dynamics. Toddlers and preschoolers are headstrong by nature. They test boundaries. That’s just what they do. It’s the parents’ job to redirect the child and show who has the upper hand. It’s exhausting and disheartening, but no one ever said being a parent was easy.

Sarah and Amy are perhaps the most well-defined characters, but both women have difficult pasts which have shaped them into the adults they later become. I would have liked to learn more about Amy’s past, especially, and learn how she became the cynical, tired, overwhelmed wife and mother Frey presents. Amy and her husband Richard (a weak secondary character who is overshadowed by his strong-willed wife at virtually every opportunity) are in a strained, loveless marriage that neither one has the energy to end. Their younger child, Robbie, is docile, obedient, and clearly Amy’s favorite. He appears in several scenes throughout the book but is very much a supporting character. (Perhaps Frey includes him to show another side of Amy’s personality—she is patient and loving with her son, in stark contrast to her short-tempered attitude toward Emma). Amy visits a counselor and tries to understand the source of her behavior, but finds no clear answers.

Besides the clear moral dilemmas Frey creates, there is no real sense of urgency in the book. The reader does not get the feeling of heightened tension or strain that is usually found in works with similar plotlines. The efforts to find Emma are lackluster at best. Her father, while a rather bland character, seems to be the only one truly concerned about finding Emma. I could not condone the thoughts or behaviors of either Amy or Sarah. Although most of us have seen questionable parenting skills and certainly sympathized with the child, it’s not a stranger’s place to decide the child would be better off with them rather than their family. Amy’s complete lack of indifference to her daughter’s well-being—as well as the relief she feels to have her gone, and her complete self-serving attitude—truly made her a despicable character in this reader’s opinion.

Sarah is not interested in harming Emma—quite the opposite. Sarah sees so much of herself as a young girl in Emma. Sarah, too, could never quite win her mother’s affection, and never understood why her mother disliked her so much. (To round out the backstory and further complicate the present situation, Sarah’s mother resurfaces midway through the book). Sarah seems to be impulsive but cannot face the consequences of her decisions. During her time with Emma, Sarah’s mother resurfaces, she avoids her best friend’s calls, she is unsure whether to sell her business for top dollar to an interested buyer, and refuses to work through her real feelings about her breakup. Focusing on Emma gives her an excuse to focus on her immediate present—away from her job and other commitments, they seem to fall away and being

Although Not Her Daughter is thought-provoking and raises some interesting moral questions, the hard-to-like characters and implausible storyline made this novel difficult to embrace.

About the reviewer: Sara Hodon is a Pennsylvania-based freelance writer whose work has appeared in over two dozen print and online publications.