Reviewed by Jack Messenger

Reviewed by Jack Messenger

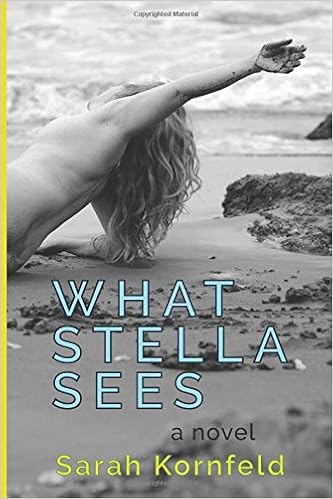

What Stella Sees

by Sarah Kornfeld

Cove International Publishers

Paperback: 345 pages, Aug 1, 2018, ISBN-13: 978-0692161579

What Stella Sees, Sarah Kornfeld’s complex debut novel, is about convergence and displacement. Above all, it is about perception: the consequences of its absence and the obligations of its presence. Young Stella is ill, it seems, with a peculiar form of epilepsy that eludes diagnosis and treatment. Her parents Rachel and Michael are in the throes of divorce, increasingly estranged from their own selves as well as one another, while they careen off specialists and medical regimes, a process that takes them from New York and San Francisco to Paris in search of a cure for their daughter. Yet Stella sees other things, too. Her seizures are a kind of vision-state in which she is able to explore the ocean depths, discovering real and imagined creatures that inform her art – the art of creating worlds of meaning inside the tiny whorls of seashells.

At its most basic, what Stella Sees is What Maisie Knew – that the adults around her are an inconstant and unreliable bunch, prone to objectify (later, commodify) her as the sum of her symptoms. Importantly, however, what Stella sees is also the return of the repressed or, at any rate, the suppressed. The past – never dead, never passed – catches up with Michael and Rachel, and later with Mo, whose cerebral palsy sculpts his body into agonizing deformations. His body and Stella’s brain enjoy a mutual self-recognition that leads to catharsis of sorts, where that which has been forgotten or buried is brought to consciousness, examined and integrated.

In truth, Stella is not drowning but waving; not simply an artist but also a scientist:

Rachel, it’s something we’ve not seen. After each seizure she comes out ready to learn! She’s not deadening, see? She reads advanced books on biology. She reads graduate and postgraduate-level research on the marine and tidal patterns …

Michael, eager to love and be loved, is able to recognize his daughter’s gifts earlier than is Rachel, who is consumed by rage at each unsuccessful treatment. The world does not always bend to our wishes, but Rachel and Michael are graduates of Yale, movers and shakers in contemporary Art with a capital dollar sign, and they are used to telling others what to think and who to buy. Yet Rachel’s rage is also a symptom of her own shame and guilt, the deep causes of which lie buried in Israel–Palestine.

There are many pleasures in What Stella Sees that one might call incidental. Rachel herself is one of them – an elegant woman whose carefully maintained façade of urbane sophistication and skin-deep friendships cracks before our eyes. Her lengthy conversation with Julian, an ageing aesthete once friends with Peggy Guggenheim and an Art Whore if ever there was one, is masterly in its delineation of character and a shifting balance of power. They both get what they want, which is somewhat less than they need and always open to reversal. Perceptions support reputations which garner income, but the whole edifice is only as solid as the latest deal, the most recent recommendation. ‘Then it happened. She forgot for a minute why she was there, what she was angling for, and what she was pretending to be. A dealer? An historian? A personal shopper; high-end, like Julian?’

What Stella Sees provokes us to ask what, exactly, is the good of art to those who cannot really see it. Isn’t it supposed to make us better people than we would otherwise have been? I am reminded of the affluent gallery trustee I once saw interrupt her conversation about the architecture of the new wing in order to stamp on a spider that had the innocent temerity to scuttle across the spotless wooden floor – an act that immediately negated all her fine words about beauty and balance.

In novels as in life, incidentals are the things we tend to remember when what seemed important is long forgotten. Michael and Rachel, for example,

learned that the strangest things count for love in a hospital room … all of them showed different forms of neglect, but also often small bits of love. When the vending machine wasn’t broken and it gave Stella a chocolate; that was love. When the social worker asked Rachel a good question and got her through the paperwork quickly; that was love. When the night nurse (at 3:45 a.m.) brought Michael a Starbucks coffee – that was true love.

These little epiphanies are what art can also provide. Although I cannot quite visualize Stella’s own artworks, nevertheless I believe them, and what they convey is very real:

Almost three years of shells: large, small, white, painted, glittery, wrapped like a miniature Christo’s or filled with poems painted carefully on the insides … the shells were artifacts and the answer to the riddle of her body: each seizure forced her into a private place that returned her just a bit harder; an outer casing that was growing calcified over time and protecting a discrete, private experience.

To his credit, Michael is much more open to these incidentals than anyone else and is moved by them: unexpected kindnesses provoke tears. And he can still talk Art, even when it comes to Stella’s shells: ‘They’re good because they utilize an archetype – the hidden architecture of shells to explore personal narratives. OK?’ Yes, we see.

What Stella Sees avoids all sentimentality about Stella’s condition. Stella is not unreservedly ‘blessed’ to be as she is. ‘She suffers multiple seizures a week. Do you understand that’s like microwaving your head three times a week on “High”?’ The seizures make her ‘smarter’ each time, so that she arrives at a ‘deeper knowing’, but they render her vulnerable to accident and injury. Nor is the novel concerned to inspire us to greater understanding and ‘acceptance’ of difference by presenting us with a brave young girl, a savant. Instead, we are shown the human, and we recognize it, incidentally and thus for always.

Sarah Kornfeld’s writing is frequently surprising and audacious, with passages of sustained concentration. She is unafraid to report how people feel when they do not know it themselves; occasionally, she hints at a future with which they cannot possibly be acquainted. This is all excellent stuff, unabashed to ‘digress’ or to break rules that are there to be broken. Most of it occurs early on while, later, the writing can occasionally slip into naïvety and redundancy, suggesting a lot of time has passed in composition or else authorial indecision has clouded artistic judgement.

What Stella Sees is a bivalve shell that turns on a hinge, and I found the first half the most interesting. I should have been delighted had the novel remained within the family dynamic and chosen to explore it in more detail. It seems to me there was a great story to be written about Stella, Rachel and Michael. Instead, the scene shifts to Paris, where the novel becomes a little diffuse, with too many things to get through and out the other side. Mo, in particular, as important and as interesting as he is, often forms an obstruction, while lengthy passages about a luxuriant techno-medical apparatus fail to resonate (at least, with me), even at the meeting point of art, science and psychology.

In short, despite many excellent qualities, the second half of What Stella Sees attempts to cover too much ground for its own good and does not quite live up to its beginnings. However, it concludes on a note that is both satisfying and disturbing. It is to do with contamination and human responsibility, and brings us back to the fragile plenitude experienced by Stella in her oceanic wanderings. Suddenly, the world is too much with us, and in our end is our beginning. Life, exhausted and bewildered, once crawled out of the sea to look about in fear and trembling. Today, depleted and poisoned, those same oceans are rising to reclaim the very thing they spewed forth.

About the reviewer: Jack Messenger is a writer and reviewer based in Nottingham, UK. Find out more about him at http://jackmessengerwriter.com