Reviewed by Mary Ellen Talley

Four Quartets

Four Quartets

Poetry in the Pandemic

edited by Kristina Marie Darling and Jeffrey Levine

Tupelo Press

ISBN 978-1-946482-44-0, 296pp, 2020

Four Quartets: Poetry in the Pandemic edited by Kristina Marie Darling and Jeffrey Levine is a superb anthology that besides dwelling on pandemic experiences, also reminds us that our current conundrums are part of a larger time warp and weft dating all the way back to prehuman time. Several anthology contributions set our public health crisis against a backdrop of natural disasters and socio-political turmoil.

Tupelo Press editors invited twelve poets to contribute pandemic related work in the form of chapbooks. In addition, over 1000 poets responded to a call from which editors selected four more twelve-page chapbooks.

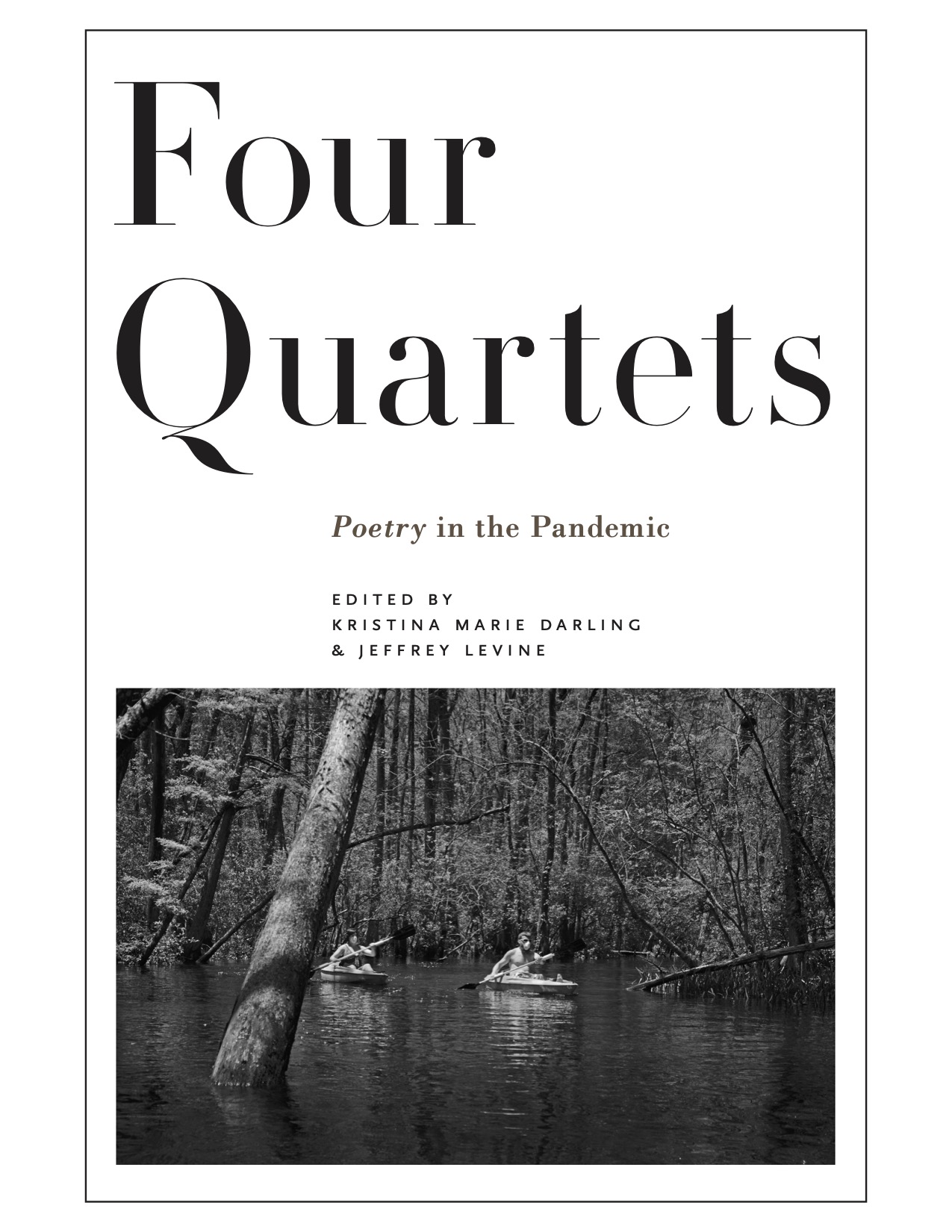

The anthology’s cover image by photography contributor B. A. Van Sise depicts two masked individuals in socially distanced boats dipping their oars into the water of a swamp. Apt visual metaphor as we navigate troubled waters of the pandemic.

In these poems we catch traces of our own experiences and feelings along with glimmers of the new vernacular that has arisen in less than a year. In her experimental juggernaut of poems, Stephanie Strickland sprinkles alliteration and assonance. Mary Jo Bang, on the other hand, uses anaphora to embed the mundane of both the new and old quotidian with her numerical progress translating Dante’s “Purgatory.”

Several poets have composed poems that reflect on Covid-19 experiences indirectly or metaphorically. Jimmy Santiago Baca’s first poem, “Poetic Prayer,” uses indigenous stories as well as history of the continent to warn readers that buffalo are coming “down the Appalachia trail and Continental Divide / grinding false patriots beneath typhoon hooves / stampeding metal weapons, money, power.” Buffalo are coming “waking people, stirring them to think / to feel again, to do away with profit margins.” Baca describes the vision of a “White Buffalo” with its voice spreading to tell us to “live as human.” In indigenous lore, a white buffalo symbolizes hope and is a sign that prayers are being heard.

Our pandemic pause may be enabling us to collectively rethink the accumulative rush of our lives. In Baca’s poem, “Buffalo Rain” we can feel gratitude as Mother Earth is given “a reprieve from our greed.” Perhaps pandemic is here to teach us again to slow down:

grass grew green, flowers bloomed

dogs sunned comfortably on patios

and since gatherings were banned

and travel discouraged, people could be seen

reading books again,

Poets Yusef Komunyakaa and Laren McClung also take readers from past time up to our present pandemic as they respond to one another’s tercets in a long piece, “from Trading Riffs to Slay Monsters.” They begin with early geologic time before man walked upright, through medieval history, plagues, the Confederacy, and prisoners in Rikers. We are forced to look upon this particular time from a larger perspective, “As doors of the Gilded Age fly open” heading toward “calamity–consumption, tuberculosis, or TB– / I also know the poor will inherit the hardest / blows.” These two poets throw out a lifeline of hope, “We know there’s no way around fate’s / finale, but, look, there’s work to do / with what little time we might have left.”

The poetry of Shane McCrae mesmerizes us with embellished repetition that crescendos in our ears as it reflects on the poet’s age and the youth of his daughter. He can’t pretend to be a teenage skateboarder any longer just as neither can a city purport to change without impact. McCrae joyfully writes in “Skating Again at Forty-Four” of accomplishing “one kickflip / On the flat in the empty park to prove I could.” This may be a metaphor for resilience of self during current turmoil as well as a good omen for his city.

Dora Malech uses the metaphor of fertility for our waiting while considering motherhood and/or miscarriage during quarantine. In the poem “Animal Crossing,” she suggests one can find solace from the pandemic in littoral spaces where she has picked up “literal litter.” The speaker points irony at herself saying, “I’m sweaty from my one good deed.” Further on:

I confess that this is not a game

and should be over, but I don’t

know how long it takes to play

what’s not a game.”

Ken Chen waxes Whitmanesque, as he includes U.S. social/political history and Greek mythology in his lengthy numbered piece, “By the Oceans of Styx, We Knelt and Wept.” Chen lists instances of violence to the poor and to people of color by police. We read in part two, that “Styx and stones, brook and bones, words will never hurt me.” He poignantly speaks of the “festive crescendo of / a globe’s loud grief.” Chen reminds us that “What we remember / replaces what remains.”

The poet Jon Davis writes poems such as “Ode to the Coronavirus” that provide images of the pandemic. “Teach me how to love the cough, the test, / the social distance, canceled prom, empty gym,” before comparisons to historical figures such as General Custer in later poems. Davis refers to current riots, protests, and floods. In “The Body is the Site of Discipline,” he writes that “Absent discipline, we languish in freedom.” Some food for thought considering those who protest pandemic restrictions in the name of personal liberty.

Writing in the vernacular of a man whose time to protest on the street is past, the poet A. Van Jordan writes as a man whose current role is to be present for his mother living with Alzheimer’s during this pandemic. In the poem “Be Like That,” he offers wisdom: “The world cares less // than you think about what you think; / we’re too busy being heckled from above.” Light humor eases the weight of Covid-19 frustrations. Sometimes Jordan deals with it all by “Reading The Tempest While the News Plays on Mute…” In this poem, he suggests a parallel between Caliban’s enslavement by Prospero as he witnesses TV reportage that a “young brother / dies, again in police custody.”

Maggie Queeney writes in lyrical resilience of being “The Patient” during pandemic with images of “Her cracking carapace, she // Lines her skull with velvet, snail shells ground into // a fine, fawn-colored powder” in the poem “The Patient as a History of Medical Treatment.”

The obscure becomes beautiful in Jae Kim’s translation of South Korean poet Lee Young-Ju’s prose poems. “This strange / reaction I have of weeping whenever the inside of my body / turns dark” resounds in the poem, “Sister.” These poems are packed with surreal images as in “Roommate, Woman,” where the speaker sees upon waking “my body has been rearranged.” Metaphor meets reality when the poet writes in “A Romantic Seat” that “He’s been siting so / long he’s become the basement.” The statistics in the news take on human psychology in “Book Club at Night” as the poet observes that “An obsession over death is proof / of wanting to live.”

Striking prose poems by Rachel Eliza Griffiths speak for those who have died because of Covid-19. In “Fever,” she writes “I burn in the frame of me, leaning against dark beams of bone.” In “Silence,” we are told “The wound of the virus is not quite / solitude but isolation.” Humanity abounds throughout these pages. In “Edge,” Griffiths reminds us how we miss touch by asking, “Can your hand find the edge of mine?” She dedicates her piece, “Flower” to a forensic technician who places daffodils on body bags in a New Jersey hospital morgue. The poem sings:

I would like to believe this poem is a daffodil

placed on the lid of a language that is trying to speak

about the world. Let this poem be a stinging like beauty

in our eyes. O city, we are living on our knees.

Let Tanisha put her flowers down into the earth. New York,

I want to save you.

With sonnets and free verse poems, J, Mae Barizo writes with feminist strength in “Sunday Women on Malcolm X Boulevard” that her sisters wonder “how long to hold onto husbands, how // to skin a chicken, how to tend a fire / that burns thousands of miles away.” In the poem “Survival Skills,” she writes of “Being able to dodge / a bullet.” It seems every apt descriptor in the vernacular is included somewhere in this collection, thus enabling readers to reflect and remember long past this pandemic.

Form enhances content as Traci Brimhall and Brynn Saito present ten modern ghazals bookended by two free verse poems “Dear Past” and “Dear Tomorrow.” The chapbook ends with hope, “Yes, there’s still a chance for us / both to be tooth and moon and wild recovery.” In an impressive riff on Ginsberg’s “Howl,” Denise Duhamel minces no words, “I saw the best minds of my generation (i.e., Fauci, Birx) / undermined by Trump.” Then she ushers readers through an epic twenty-three stanza “Pandemic Pantoum” that captures bits that we will delight in and/or cry about in recalling, such as, “There’s no toilet paper to be found in stores / but I did score some Kleenex on Amazon.”

The anthology contains three distinctly varied diary type chapbooks. One is a visual contribution is by B. A. Van Sise. From his daily practice of documenting each day by taking one photo, he has selected twelve photos to cascade down twelve pages. This layout is echoed by Rick Barot’s final chapbook in the collection. His diary observations during the pandemic also cascade down twelve pages. Barot writes in “#13” of listening more during the pandemic. His mention of an “old-fashioned thermometer” might seem out of the blue. However, years from now, we will recall that so many people were buying digital thermometers during the pandemic that drug stores couldn’t keep them in stock.

The other diary type chapbook earlier in the collection is that of Mary Jo Bang. Her extensive anaphoric list captures the relentless essence of her/our pandemic experience and how people endured:

Today, the world outside continues to be one of protests.

Today, worn away by this work and by the world.

Today, corrected the notes for Purgatory XXXIII and Purgatory

XXXII. Revised Purgatory XXXI and Purgatory XXXII.

Sometimes it all blurs.

The pandemic has made time blur for people. This anthology offers a variety of excellent poems by an inclusive array of artists to help us remember and acknowledge how we coped (or not.)

Just as T. S. Elliot’s “Four Quartets” were originally published as stand-alone works, the chapbooks that make up this anthology by the same name can be savored separately even as we appreciate how they weave and intersect. This anthology will resonate and shine in the future as a historic literary gem.

About the reviewer: Mary Ellen Talley’s reviews have been published in Colorado Review, Sugar House Review, Entropy, Crab Creek Review, and Compulsive Reader. Her poems have been widely published in journals such as Raven Chronicles, Gyroscope and Ekphrastic Review as well as in several anthologies. A chapbook, Postcards from the Lilac City, was published by Finishing Line Press in October 2020.