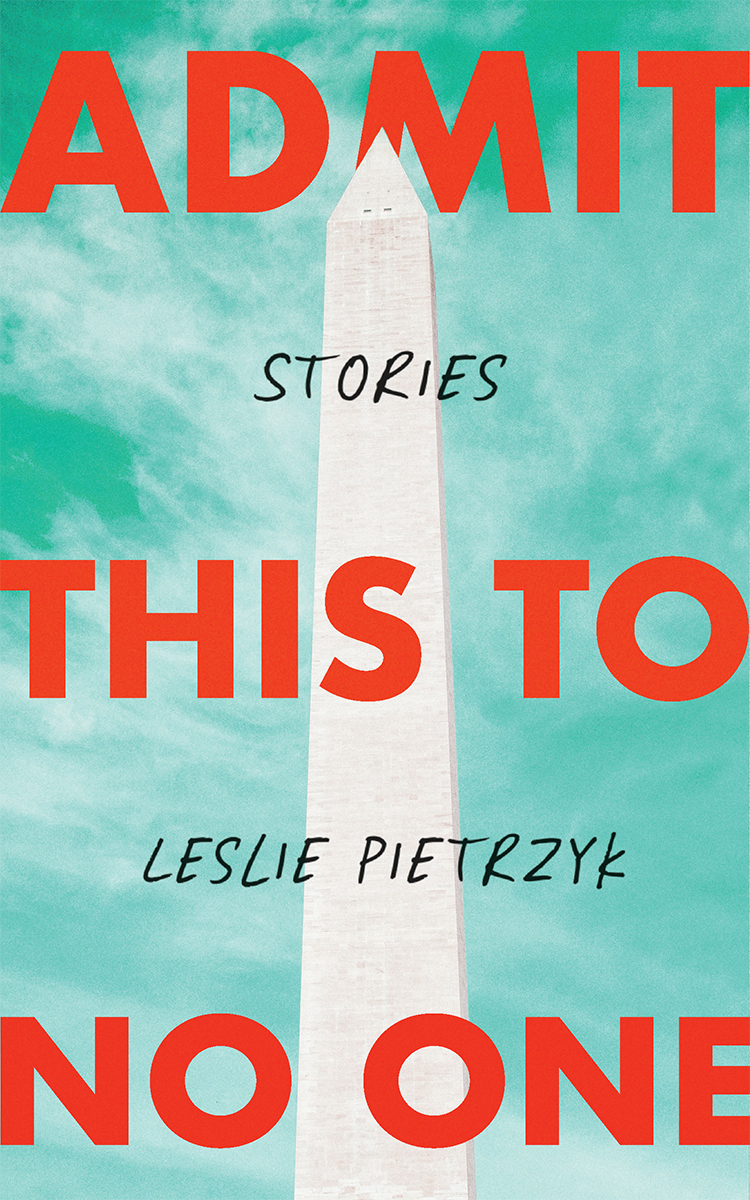

Admit This to No One

by Leslie Pietrzyk

The Unnamed Press

November 2021, $18, 266 pages, ISBN: 978-1951213411

The fourteen stories that make up Leslie Pietrzyk’s unique collection flesh out the social and bureaucratic power dynamics that define Washington DC culture. Two-thirds of them also tell the story of the messy lives of a group of women surrounding the Speaker of the House of Representatives, the unnamed third most powerful politician in America, a man who feels like a combination of Bill Clinton and Teddy Kennedy blown up to even greater proportions.

The collection begins in the voice of his 15-year-old bratty daughter Madison, product of his second (or third?) marriage, who is meeting the Speaker at the Kennedy Center, where they meet once a month to “culture her up,” as if this were part of a divorce agreement. There’s tension, of course, resentment, but at the conclusion of the story, Madison instinctively shields her father when a man at the bar whom she originally suspected was making a pass at her, a “conspiracy nut,” upset by the Speaker’s atheism, attacks him with a knife. (We only learn the man’s motive in a much later story, “Kill the Fatted Calf,” told by Lexie, not in this story, “‘Til Death Do Us Part.”)

Throughout the rest of the book, particularly in the three stories involving the oldest child by his first marriage, Lexie, a photographer, the Speaker’s in critical condition in a hospital, but we assume he survives. Or at least he’s not reported dead even in stories that take place years later (stories narrated by Madison, still pretty much a brat at the age of twenty).

Three of the stories are told from Madison’s perspective, three from Lexie’s. Both women have serious “daddy issues,” of course, manifested in their relationships with men. Still a teenager, Madison is the mistress of a character identified only as “lobbyist-man,” a powerful DC player with children her age, though in the final story, “Every Man in History,” she seems to be aiming for something more authentic with a sketchy character named Dak.

We first meet Lexie, the day before she turns forty, having sex in a parking garage with her 24-year-old former student, Tay. (This scandal costs her her faculty position.) They are on their way to a gallery in Durham where an exhibition of Lexie’s photographs is taking place, the gallery owner, Chita, working overtime to sell Lexie’s work. It is here that Lexie learns that her father has been attacked and may be dying. Her reaction to the news is complicated. She hasn’t spoken with the Speaker in a decade. Impulsively, she decides to leave the gallery and drive up to DC, four hours away, with her young boyfriend Tay. Toward the end of this story, “Stay There,” Lexie observes, “All these years it was so easy, saying, ‘my father is dead to me,’ because he wasn’t dead.”

In two other stories later in the collection, “My Father Raised Me” and “Kill the Fatted Calf,” we follow Lexie on her odyssey north to her father’s bedside. In the first, having split up with Tay at a truck stop on the interstate, she stops in on Vaughn, an old boyfriend from her salad days in New York, now a successful novelist in a complicated marriage of his own, complete with a sullen teenaged son. It’s late and she’s exhausted and just needs a place to stay. Riiiight! In this story, Lexie constantly quotes her father, spelling out his advice and wisdom. (“Information is currency, according to my father” and “Make them come to you, is my father’s motto, famous now on Capitol Hill” are two of a dozen of the pearls she cites. “Keep complications simple” is another.) The Speaker has definitely been in her head all these years, estrangement aside.

In “Kill the Fatted Calf” Pietrzyk has Lexie lie to Mary-Grace, her father’s formidable handler (elsewhere referred to as “She-Beast,” Mary-Grace is the protagonist of several of the stories) and to “#4, the ‘this time it’s love’ wife,” telling them she is pregnant, in order to gain access to her father, who is lying in a coma in a hospital bed. Characters telling lies is one of Pietrzyk’s true strokes of genius in Admit This to No One. In my favorite story, “Hat Trick,” which also features a sullen teenager – this one, Ben, a neo-Nazi sympathizer – the characters are constantly lying to each other.

Told by a third-person narrator but focusing on the character Kasey’s point-of-view, it’s the story of two college roommates reuniting after fifteen years, to attend a Washington Capitols hockey game. Kasey’s friend Ari has an extra ticket because her fiancé, “The Douche,” has broken up with her and Ari has a spare ticket to the playoff game. (Kasey later speculates that the Douche left Ari because of her teenage Nazi son – and who wouldn’t?)

Ben, who wears a Kobe Bryant jersey to honor the basketball player who recently died in a helicopter crash, is the product of a one-night stand in college with a basketball player. Ari has told Ben that Kasey had recommended an abortion, which led to their drifting apart from one another. This, of course, amps up Ben’s natural hostility. He also tells Kasey, a K Street lobbyist herself, the story Ari told him about “My real father. Her college boyfriend. The musician.” This is a lie Ari stole from Kasey, who’d had a crush on that musician in college. Kasey is infuriated that Ari stole her story, and she tells Ben, who has asked her what she knows about the musician, “Yeah, I knew him. He was Jewish. Exactly who your Nazi pals hate.” Ben is gobsmacked by the lie! Kasey leaves him stewing to get a box of popcorn at the concession stand.

This story also hints at the racism that’s at the basis of so many of these stories, the racial divide that’s part of Washington’s power structure. “Wealth Management,” “This Isn’t Who We Are” and “Green in Judgement” all involve white people guilt about Black people.

What really unifies this collection is all the characters who are in denial and/or honestly trying to suss out who they really are, how they fit into their bureaucracies, their families, the society in general, their authentic selves. It’s a very contemporary collection, too, with references to January 6 and a character named “The Dealmaker” who is plainly Donald Trump. In the title story, which deals with her father’s career-ending scandals, Lexie observes, “Anyway, after the Dealmaker blows through, no scandal matters and the Speaker’s cynicism solidifies.” Admit This to No One is a truly breathtaking read.

About the reviewer: Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore and Reviews Editor for The Adirondack Review. His latest book, Catastroika, was published in May 2020. A chapbook of poems, Jack Tar’s Lady Parts, is available from Main Street Rag Publishing. Another poetry chapbook, Me and Sal Paradise, was recently published by FutureCycle Press. An e-chapbook has also recently been published online Time Is on My Side (yes it is). Another chapbook, Mortal Coil, is forthcoming from Clare Songbirds Publishing.