Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

Reviewed by Magdalena Ball

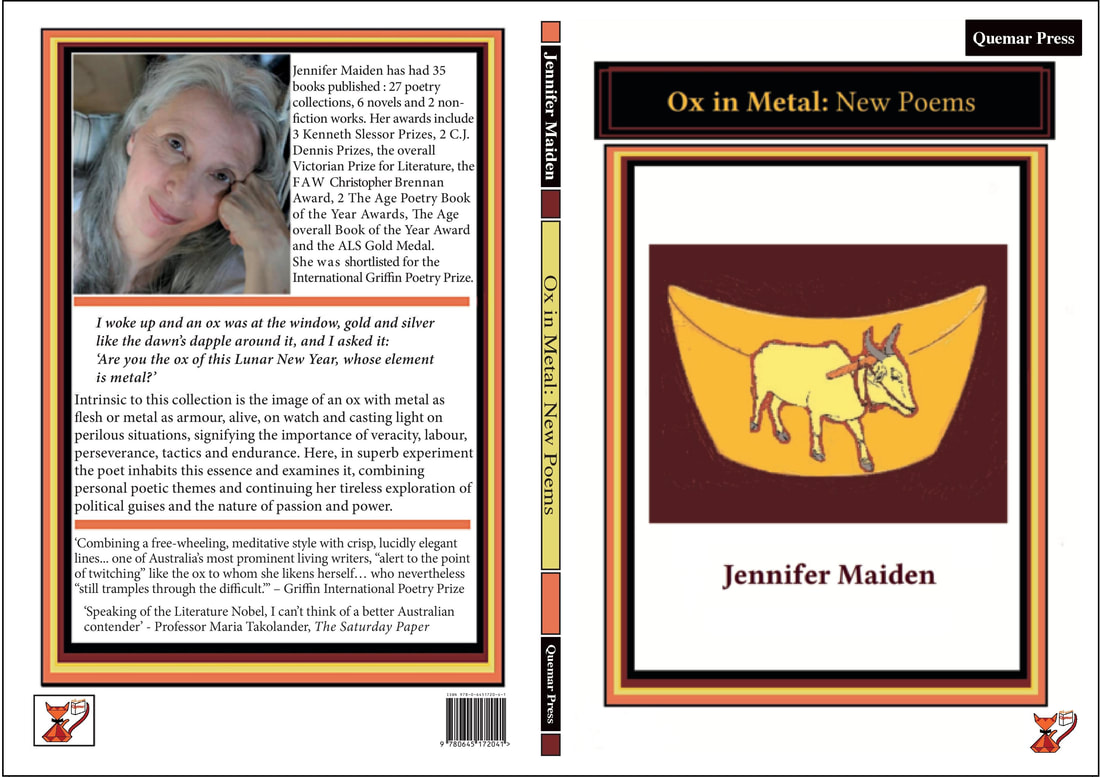

Ox in Metal: New Poems

By Jennifer Maiden

Quemar Press

2022, ISBN: 978-0-6451720-4-1, $18.40, 80 pages

Jennifer Maiden continues to turn her razor-smart poetic eye to politics and power in her new book Ox in Metal. As with her previous books, Maiden has a knack for combining often disparate characters: fictional ones such as her own Claire Collins and George Jeffreys or Brookings the Pombat (wombat and possum crossed) with real ones like Hilary Clinton, Malcolm Turnbull, Julian Assange, Joe Biden and even the poet John Donne. Maiden fans will recognise the progression. It’s as if there’s a dream-universe in which the characters continue to develop like a series—they meet and talk, referencing previous situations and combining those with what is happening in the real public and political spectrum. The effect is both stimulating and unsettling, as the characters are both representative and self-contained.

As the title suggests, the book pivots around the metaphor of the Ox, which has multiple meanings. In metal the Ox is symbolic of tenacity and strength, a kind of fierceness, as in the title poem, which sets up many of the themes in the book: free speech, the nature of power and all of its corruptions, money and its many forms and abuses against the the counter-power of poetry. This is all woven deftly—the lustre of golden skin vs the stock exchange, the dollar and crypto currency, while still allowing the ox its sentience as a creature. Like many of the poems in the book, this one references Maiden’s other works, in this case the poem “Year of the Ox”, from Maiden’s book Liquid Nitrogen. The other symbol of the Ox is a kind of earthy reliability and deep seated patience, a motherliness which is also aligned to the power of poetry – a different form of power. These symbols are not opposites but rather exist side-by-side in a tension that charges the work.

The book employs a range of Maiden’s tropes, such as the diary poem, historical and fictional characters that “wake up” in a variety of modern places to contemplate current affairs, and the narrative poem that utilises quotations, prior publications or things other people have said. Throughout the book a kind of alchemy happens where these often odd conjunctions meld to form something entirely novel: past and present history, virtual reality and face to face meetings, dreams and waking moments, off-the-page politics and the fictional universe. It’s often so fast paced that you are forced to slow yourself down, ensure you’re reading at the right depth, cross-checking the references and engaging fully, but doing so is a rewarding experience that is lightened somewhat by the metapoetic nature of work, which often pulls back to provide a moment of lighthearted self-awareness. This comes through in flashes of whimsy against Maiden’s sharp analysis, poignancy and humour sitting side by side, as Biden Skypes one of her fictional characters George to talk about his feelings of guilt about the Middle East, or as a personal meditation on the racism of May Gibb’s Banksia men:

May Gibbs drew Banksias with the untamed

accuracy only a preserver could,

Namatjira ghosting gumtrees from his blood.

It all boils down to Bib and Bub and what

bears down on them from the enchanted wood. (“Blocking on the Banksias”)

The poems are often elaborate and breathless, moving in and out of literary analysis, history, biology, and current affairs seamlessly. John Donne rewrites the assassination of Qasem Soleimani in a long sentence that evokes Ghislaine Maxwell, the Country Women’s Association, and Mossad – the Israeli Intelligence Agency:

If Donne were concocting a synthesis from last night’s news, he might

say that the Israelis using Trump to assassinate General Soleimani

killed the civilised top predator they could talk to, the one

dedicated to fighting Isis, and therefore they left a plague

of Arab resentment which when they provoked it rose in misery

beyond words, and that his metaphor was completed by the mice

the NSW Government, having killed top predators like the dingo, fox,

and the cat, wants to use banned poison to destroy,

risking native animals, water, pets and wheat. (“Doctor Donne and the Country Women”)

Of all of Maiden’s books that I’ve read, this is the most self-referential, breaking the fourth wall and bringing in memories, quotations from reviews of her books, referencing readings, memories, moments, and things other people have said about her:

Once

after watching me at a reading Chris Mansell said

she was impressed by the calmness of my hands in repose,

as most people’s are more active, anxious. (“Extra Time”)

The work is so broad, moving between galaxies, the Tibetan Bardo (out of which comes Eleanor Roosevelt), Blockchain, spy software, RNA technology, Covid vaccines and many literary references from the work of Edna O’Brian toThe Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, Fifty Shades of Grey to Greek Mythology. All these references notwithstanding, it is clear that Maiden is working in the realm of the poet, creating something that is neither invective nor philosophy, but rather creative:

It’s hard

to make this lyrical, although I suppose there is

always something lyrical about knives: the manner

in which they scatter light back but still seem

to have their own bright vector. (Diary Poem: Uses Of Iron Ladies)

Maiden’s humour is on full show throughout, with flashes of insight mingling with wryness that feels conversational and intimate, as when exploring the financial data leaks “Panama, Paradise and Pandora”: “Perhaps soon to become a rom-com on witch-siblings”. There are also personal explorations, memories and recollections, as well as a recognition of the unreliability of these recollections. As always, humour mingles with philosophic pondering, the real playing against the virtual with self-referential modernism:

It might be good to be reading in Canberra

in that long-ago sleet winter, and as I begin

my poem two women from a car come in:

running late, but it may not matter. (“Where was I?”)

Ox in Metal is not a difficult book to read, but it certainly will stretch the reader’s awareness of world political events, encouraging a deeper and more critical engagement. The work is often lyrically beautiful, but it always resists the easy denouement. Maiden is no ivory tower poet. Her work charged by the world, always up-to-the-minute, always challenging and always powerful.