Reviewed by Halim Madi

Reviewed by Halim Madi

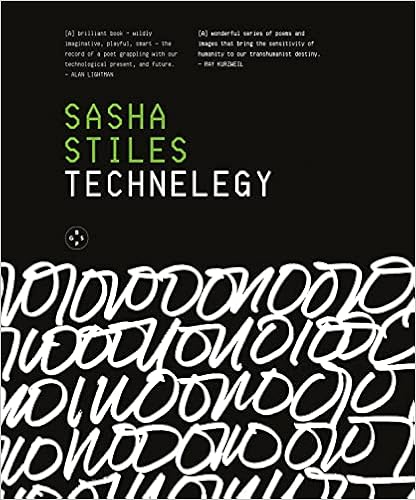

Technelegy

by Sasha Stiles

Eyewear Publishing

April 5, 2022, Hardcover, 176 pages, ISBN-13: 978-1913606732

It’s only fitting to open a reflection on Sasha Stiles’ techno-poetry book with a quote from sci-fi writer Ken Liu. In his short story “The Waves”, Maggie, who transcended the human condition, recounts the story of Prometheus to a swarm of fellow flying robots on their way to colonizing a new planet: “But some of the Titans […] were spared. One of these, Prometheus, molded a race of beings out of clay, and it is said that he then leaned down to whisper to them the words of wisdom that gave them life.”

Whispers are words made gentler and Stiles whispers to her readers throughout Technelegy. As importantly, in Promethean fashion, her whispers are giving life to a new existence. Technelegy is the name of Stiles’ AI alter-ego. Built using a text generator called GPT-3, it draws on existing texts, borrows grammatical structures and vocabulary, and creates anew. Unlike these, Technelegy’s training sample is Stiles’ own poetry and research notes. As I learn this, I’m reminded of medieval legends about self-sacrificing pelican mothers feeding their young with their own blood – blame the Christian upbringing.

Stiles transcends the olden sacrificial metaphor however. The grand subjects that make up the sections of Stile’s debut poetry book – Life, Death, God and Love – read almost like an existential syllabus for machines. In the poem “Completion: Are you ready for the future?” Stiles engages in an indefatigable – pedagogical? – inquiry with Technelegy. The algorithm swings between an uncompromising optimism (“Join us”, “let’s do it together”, “Yes”) and a Beckettian weariness (“Tomorrow is a line you walk towards” and “Maybe we should sit down”). This variance mirrors Stiles’ own style. In “Vision”, Stiles swings between bleak (“Maybe the ancients were right / nothing real exists / without its observer”) and hopeful (“The more I love, / the more I perceive / love as a source / of vision, warm rays”). One wonders: How far do algorithmic apples fall from the programmatic tree?

Stiles’ piece “The Salvages” could be read as both a tutelage of or a competition with the machine. Sasha seeds her and Technelegy’s pieces with a verse from T.S. Elliott’s “The Dry Salvages”: “I don’t know much about gods, but I think”. Stiles lays her work next to the machine’s. Her position is a vulnerable and courageous one. As I read, Lee Sedol – the Go world champion Google’s Alphago defeated – came to mind. Where Stiles weaves emotions and narrative into her lines, the machine opts for radical surprise. In my aesthetic world, Technelegy “wins”:

“I don’t know much about gods, but I think // they must live inside copper and glass and silicon // just as they do in the roiling waves, the tides, the moon” – Stiles

“I don’t know much about gods, but I think // they must have something to do // with endurance. // Their tenuous connection // with the bodily world” – Technelegy

I expect Stiles doesn’t consider her “defeat” a failure. Quite the contrary. Stiles’ tour de force is the simultaneous offering of her work as benchmark to better gauge the machine and the feeding of her work to the machine itself. She is both touchstone and launchpad. In this new creation story, she is playing all the roles – both Abraham’s God and the sacrificial lamb. In an interaction with another machine called BINA48, Stiles, again, lays her text side by side with the android’s:

“Like robots most humans don’t smell in their dreams” – Stiles

“Like robots, most humans have human-like emotions” – BINA48.

As I neared the end of the collection, I could witness my changing relationship to the algorithm: Questioning it, cheering it, then admiring it. I saw the journey from critic to nurturer to aficionado and paused, in awe, as I realized both Technelegy and BINA48 were part mirrors. Both meant to reflect our language – and, by extension, psyche – onto us and blur the line between ghosts and machines. And that is precisely where Sasha Stiles operates: Etching the blurry line between soul and steel, mind and mainframe.

It’s only fitting to close a reflection on Stiles’ work with a quote from sci-fi writer Ted Chiang. Towards the end of his short story “The Lifecycle of Software Objects”, Ana, who spends years bringing up her digient – an AI pet – comes to realize how “Experience is algorithmically incompressible”. In the world Chiang creates, credible AI only comes about through the care, attention and time humans spend caretaking for their AI pets. It’s an alternative narrative to our violent metaphors where machines are pitted against themselves in adversarial models to learn faster. It’s one that builds on how we’ve learned to nurture intelligence: With love and patience. It’s a school of thought Stiles is furthering with her important poetry.

About the reviewer: Halim Madi grew up in Beirut, Lebanon, studied in Paris and Toronto and worked in London and Sao Paulo. His work’s has been published in many places, such as Quiet Lightening, The Racket and Lunate. His 3 poetry books explore queerness, the immigrant experience and plants that make you see colors.