Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

Reviewed by Charles Rammelkamp

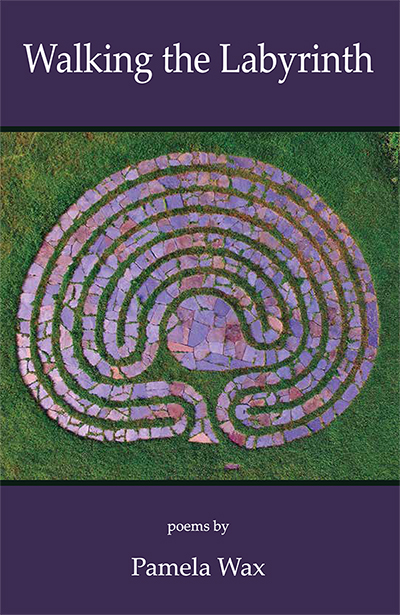

Walking the Labyrinth

by Pamela Wax

Main Street Rag Press

May 2022, $15.00, 96 pages, ISBN: 978-1-59948-919-3

When her father dies three years after her mother, Pamela Wax writes in “Gazing into the Abyss,” a rabbi tactlessly tells her, You’re next, aiming for stoic wisdom instead of comfort. It’s time to face your own mortality. Pamela Wax stares mortality in the face throughout this collection, an extended elegy for her younger brother who committed suicide, as well as for her other dead – parents, grandparents, aunts, friends. She wrestles with death like Jacob wrestles with the Angel. The poem concludes:

At sixty, I’m still generationally

misplaced, having friends jam-sandwiched

between busy lives of children and grandkids,

and/or needful parents who fall,

forget, can’t hear, or swallow, while I have

neither parents nor children. I look out

at the abyss, and wonder if this makes me

more ready to be next, to parachute

a gentle landing into a world-to-come.

As Saul Bellow memorably wrote in Herzog, “…nothing faithful, vulnerable, fragile can be durable or have any true power. Death waits for these things as a cement floor waits for a dropping light bulb.” Yet grief and guilt are automatic responses even as the inevitable occurs.

Mainly, it’s her younger brother Howard’s death by suicide that haunts Wax. It is either implicitly or explicitly the subject of over a dozen and a half poems. Walking the Labyrinth is dedicated to Howard’s memory.

In the very first poem, “Howard,” Wax breaks down the name into its syllabic units, “how” and “ward.” How – the first word in the Book of Lamentations, read every year on Tisha B’Av, a day of grief in the Hebrew calendar. How awful. How / I wish I’d known. Gradually, through “My Friend Dreamed About Me Twice,” “The Day After He Called,” and “Approaching Zeal: A Run-On Abecedarian,” we learn about Howard’s tragic death, jumping from a bridge, May 12, 2018, his body found twelve days later, the notes he left for his sisters, his husband and their children. All of this is saturated with Wax’s grief and guilt. In “M’aidez” and elsewhere she laments having missed the warning signs, the cry for help.

Three of the poems – “May, Mother, I,” “The 42nd Day of the Omer, 2020,” and “Crossing the Breakwater” – take place on Howard’s yahrzeit, the anniversary of his death (Iyyar 27 in the Hebrew calendar), always a moment for reflection. In “May, Mother, I” she writes:

Howard-less, I dread the coming

years we would have seasoned

together into wrinkles and salvaged ease,

playing Scrabble on a porch swing

in some fairy tale future, reminiscing

like an old married couple….

In “Cloven Hooves” Wax recalls her father’s death, the first night of shiva, and she recalls both her mother’s and her father’s deaths in “Ethical Will.” In “Nacre” it is her Aunt Pearl, after whom she was given her Hebrew name, Penina. In “We Flew Pan Am” she again recalls her mother’s passing. “Oman-Ray Uins-Ray” also involves her parents dying. “Seeing Red in Hopkins Forest” is a meditation on her beloved college professor’s suicide. In “I Am Not Descended from Stoics Like Jackie O.” she recalls her grandfather dying on her eleventh birthday, and two years later, when she becomes bat mitzvah, her grandmother imploring

for a death more attractive

than the diapers and wheelchairs

that had welcomed her to The Jewish Home.

But in other poems the topic is joy. “I spoke about joy on the evening / of his second yahrzeit,” Wax writes in “The 42nd Day of the Omer, 2020.” In the final poem, “Gleanings from the Field,” she cites the verse from Psalms 126, Those who sow in tears will reap in joy. (“Perhaps it’s relevant that my middle name, / quixotically, is Joy,” she observes in “Approaching Zeal…”). “Crossing the Breakwater” ends on a joyful image: “I recited Kaddish / with and for my brother, and we praised the One who split the sea / so we could cross and look back with wonder.” “Dancing with My Brother” is likewise joyful “Custom coaxed / me to mourn, but he invited / me to dance.”

An ordained rabbi, Pamela Wax’s poems are steeped in ethical concerns and Jewish tradition and practice. “I keep getting books about character,” “Not Moses,” “Bad Girl” and others address her sense of coming up short, failing in her duties as a sister and a daughter, as a human being. One’s responses to grief are complex and often contradictory. Throughout Walking the Labyrinth Wax confronts her ethical and moral reactions, feelings, behavior. In “My Brother’s Shomer,” implicitly identifying with Cain, the first murderer, she goes poetically through the ritual of preparing the body for burial. “The Tenth Man” and “Mo(u)rning Minyan” also take on the rituals of sorrow and remembrance.

Which brings us to the title poem, the image of the labyrinth. Wax writes that “a maze

confounds, a labyrinth uncovers

the self, meditation in motion. It resembles

a womb, a brain, a fingerprint, the revolving

planets, the primal and timeless.

Her labyrinths “get me / where I’m going, which is now here / and nowhere in time,” and they enable her “to remember that the one / way in is the only way out.”

Death is not necessarily final. In a number of poems, she speaks to her dead. We’ve seen her reciting Kaddish with Howard in Provincetown, and she starts “Deer, Rabbit, Robin,” with the lines:

Don’t think me woo-woo for believing

I see loved ones – the dead ones – alive,

even if not in human form.

My brother shows up as a rabbit.

His Hebrew name was Tzvi,

but he never comes as a deer.

Her mother does, however. “A doe so close, unafraid, I knew / she was my mother.” Her father, Hershel, occasionally shows up as a robin. In “Aunt Helen Chats with the Dead” Wax writes:

I was twelve, amazed that she spoke

with my uncle as if he were there.

Does he hear you? I asked. Of course.

He talks to me, too.

The poem concludes: “I was learning to walk new worlds with the living, / an apprentice training to commune with my dead.”

Walking the Labyrinth is a deeply meditative and spiritual coming to terms with death and with grief, from both a Jewish perspective and a universal point-of-view.

About the reviewer: Charles Rammelkamp is Prose Editor for BrickHouse Books in Baltimore and Reviews Editor for The Adirondack Review. His latest book, Catastroika, was published in May 2020. A chapbook of poems, Jack Tar’s Lady Parts, is available from Main Street Rag Publishing. Another poetry chapbook, Me and Sal Paradise, was recently published by FutureCycle Press. An e-chapbook has also recently been published online Time Is on My Side (yes it is). Another chapbook, Mortal Coil, is forthcoming from Clare Songbirds Publishing.