Reviewed by Elvis Alves

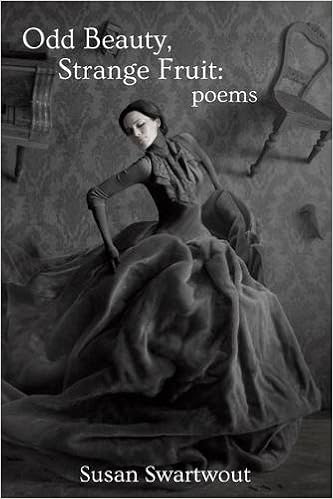

Odd Beauty, Strange Fruit

Odd Beauty, Strange Fruit

by Susan Swartwout

Brick Mantel Books

Paperback: 68 pages, October 1, 2015, ISBN-13: 978-1941799055

From Louisiana to Honduras, Susan Swartwout covers much ground in her poetry collection, Odd Beauty, Strange Fruit. The collection is billed as a gothic take on Southern culture, and in some aspects it is, but there is more here than meets the eyes or first reading. The collection also tells a family’s history and the impact of this on the life of the individual who tells it.

Swartwout draws attention to the strange world of the traveling show where human beings are on display to be viewed by other human beings at fairs. In one of these performances, a cattle prod is placed close to the “tenderest part” of a woman’s body (Tenderest, 11). Swartwout reveals certain things about the woman, “…a scrawny woman whose bones knuckle creped skin, her face lined mask of a thousand farm wives: she reveals no opinion” (Tenderest, 11). In Siamese Twins in Love, she writes about the love and family life of a set of twin performers, Chang and Eng, “you marry, buy American homes only blocks apart” (34). The same set of twins face addiction and other travails, to the point that one buries the other, “Poe never told this story: the dead body cell-stitched to your own, the other grave you were born to” (Blood’s Inkwell: Eng Writes Chang’s Eulogy). What Swartwout does here is give not just name but a story to those on display. In doing so, she wants to create empathy for them. That empathy starts with the self. Therefore, these characters tell us about who we are.

This revelation is evident when Swartwout tells us about a brother’s attempt at suicide, “ten years later he’ll try braking his own heart, a handful of pills between his words and my understanding of loss I never imagined” (Little Brother, 22). Braking here refers to stopping as when the brakes are applied to a car or when the heart stops beating at the time of death. The reader also grows empathy for the young girl who was snatched from Southern life and culture in Louisiana and thrown to the cold wind in Illinois, due to an employment opportunity for her father.

Chicago was gray/black and dark red. Mother, me, sister, and brothers

in thin cotton coats staggered from the train tipsy with Loop wind,

stopped in the cold by a drunk who wanted to carry my blonde sister

through filthy snow (Boogie Land, 25).

I prefer these poems due to their autobiographical flavor. They are sandwiched between the traveling show poems and those that deal with the author’s travels to Honduras.

The Honduras poems have what one would expect. They run the gamut of the author’s interaction with the native people to the doing of what appears to be service work; painting a church. In The Ceiba Tree, Swartwout writes of her encounter with poverty in Honduras, “His too small shirt might have been red and white once. Orphan of God/maybe six years old lies on the sidewalk, his face pillowed by cement. He wears only the shirt” (51). This scene recalls the necessity of empathy as mentioned above, a theme that is pervasive in Swartwout’s work. However, it also makes me think of why the author chose to paint this picture in Honduras and not in her country. After all, she is from the South, a region of the U.S. marked by slavery and its aftermath.

Let me be clear here. Billy Holiday’s Strange Fruit begins “Southern trees bear strange fruit/Blood on the leaves and blood at the root/Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze.” This is an anti-lynching song. An informed reader cannot read a book that references this title and that is set in the American South (for the most part) without making the connection. This connection, however, was missed by Swartwout. The fact that she did not make it is disappointing. The title poem, “Strange Fruit”, refers to the author’s brother (a valid claim that I respect). Yet, this title carries so much weight that to bypass its significance, as does Swartwout, is incomprehensible.

About the reviewer: Elvis Alves is the author of the poetry collection Bitter Melon (Mahaicony Books, 2013). Find out more at www.poemsbyelvis.blogspot.com