Reviewed by Ruth Latta

Reviewed by Ruth Latta

The Reason for Time

by Mary Burns

Allium Press of Chicago

Paperback: 216 pages, ISBN-13: 978-0996755818, March 2016

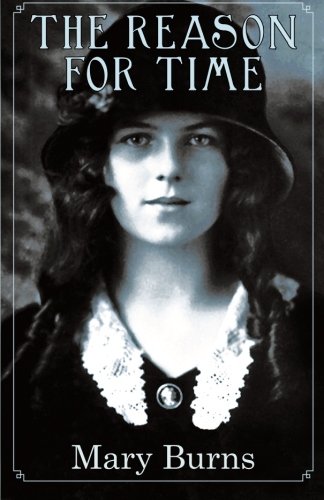

The Reason for Time, Mary Burns’s fifth novel, is a work of art, starting with the cover. The cover features an historic yet timeless photo by Mathew J. Steffens, known as “Portrait of a young woman”, who could be Maeve, the narrator/protagonist.

Burns’s novel is set in Chicago in 1919. Her choice of poem to quote at the beginning and set the tone for the story is inspired. “Working Girls”, by Carl Sandburg, is about the “river of young woman-life” in that city, as factory and office girls headed off to work each morning. He contrasts the “green” stream of young innocent energy with the “gray” stream of more experienced women who say, “I know where the bloom and laughter go, and I have memories.”

Twenty year old Maeve Curraugh moves from the “green” stream to the “gray” as a result of ten eventful days in July 1919. As the novel opens, Maeve has just narrowly escaped death in an explosion caused by the dirigible Wingfield falling on the Illinois Trust and Savings building, from which she has just emerged.

Recounted in a vivid conversational style, with Irish phrasings that show Maeve’s heritage, the novel continues with her streetcar ride home, where a handsome young conductor named Desmond Malloy chats with her and gives her a copy of the Chicago Tribune. Though conductors are known to be “terrible flirts”, Maeve accepts the paper; indeed, she is very interested in the news and thinks about what she hears and reads. Newspaper headlines are a motif throughout the novel.

Through Maeve’s heart and mind, we see what she sees, and experience the thoughts and memories that pass through her head. (This technique is not strictly “stream of consciousness” or “interior monologue”, since the novel also includes scenes and dialogue). Maeve’s allusions to past incidents encouraged readers to keep reading, to find out the circumstances of her coming to America with her sister Margaret.

The author takes Maeve, and the reader, through ten dramatic days involving a dirigible crash, a little girl’s abduction and murder, race riots, and a streetcar strike. Burns’s thorough research into Chicago history is never obtrusive but comes through naturally as part of what Maeve sees, hears and thinks about during the course of her day.

Maeve’s situation is heart-rending in many ways. She and her sister, a garment-worker, share a tiny bedroom where they make tea and boil eggs on a gas ring. They sleep in the stifling heat on a straw pallet and line up with other tenants to use a bathroom. Maeve is delighted when Desmond Malloy lets her on the streetcar for free because the five cent fare will buy her something to eat. Though she and Margaret dream of visiting Ireland, they don’t make enough money to save for the trip. Maeve’s brief engagement to a young man named Patrick Dwyer ended with his death in the flu epidemic of 1918-1919.

Maeve is employed as a catalogue order clerk with the Chicago Magic Company, a firm that sells crystal balls, wands, cards and other equipment to the many magicians who pass through Chicago on the vaudeville circuit. Maeve gives some credence to the supernatural, and when Desmond invites her to dinner and to go swimming at a Lake Michigan beach, she believes that he was destined to be her future husband. The swimming invitation requires a bathing suit, though, and where will she find money to buy one?

Though naive and innocent about Desmond, Maeve is shrewd in other ways. In brief flashbacks we see how she got herself and her sister out of working in a Florida orphanage run by the nuns who brought them from Ireland. Though Maeve is not exactly honest to the core, she is an appealing character because of her resourcefulness and her practical, broad-minded philosophy.

Racism is rampant in Chicago in 1919, with white workers angry at the flood of African Americans from the south who have moved north and are competing with them for jobs. While most of the people she knows are racist, Maeve is not, because of her love for the African American babies she helped care for at the orphanage. Nor is she judgmental when she learns that one of her co-workers, a white girl, is dating an African American real estate agent.

Maeve is surprisingly open-minded, considering her background, and her inclusive attitude benefits her at the end of the story. She reflects that “The Virgin, who kept her title though she gave birth, had to understand how it could be for a girl alone in the city, and all she needed, and wouldn’t a man make it a better life…” Later, speaking of erotic attraction, she thinks: If God didn’t want us to feel like we did, why had he given us these feelings?”

Matters come to a head when the race riots and transit strike plunge Chicago into chaos, in which Maeve loses Desmond. Throughout most of the novel, the reader walks hand in hand with Maeve in the present of the novel. Near the end, however, Maeve the narrator distances herself from the action, letting us know that she is looking back on the past as a mature woman. Following a startling ending, an epilogue ties up loose ends and shows how things work out for Maeve and Margaret.

Mary Burns grew up near Chicago but now lives in Canada. Her remarkable historical novel is published by Allium Press, which specializes in historical novels about Chicago; fourteen, by other authors, are listed at the end of The Reason for Time. Fans of Sara Paretsky’s V.I. Warshawski mysteries, set in Chicago in the early 21st century, may enjoy reading about that city a century earlier. The Reason for Time will encourage readers to delve into these other works about life in a major American industrial city.

About the reviewer: Ruth (Olson) Latta (M.A., History, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON) is working on two novels set in early 20th century Canada. Visit http://ruthlattabooks.blogspot.com